Node.JS optimizing I/O with streams

We always heard about how Node.JS is very good to build I/O intensive applications. A couple weeks ago, I found myself on a situation where I got the chance to improve an I/O Intensive application performance. But first things first, what does I/O intensive actually means?

I/O intensive

I/O stands for input and output. An input/output process could be a database reading/writing, a file reading/writing or receiving/sending network requests. An I/O intensive application pass most it's the time sending or waiting for data and this is what web servers mostly do, example: A web server receives a HTTP request, queries a database, logs info into a file and then responds the request. The pipeline described is a series of I/O processes. Now the question is, why is Node.js suited for I/O intensive applications?

How does Node.JS handles I/O?

I once had a boss who wasn’t fammiliar with Node.JS, he had been a Java developer for years now. Everytime we talked about Node.js he asked how can Node.JS use a single thread model and still be a good tool for writing web applications. The foundation of my old boss’ question is the same as ours question now. How can Node.JS handles I/O with it’s single thread model?

The classic way

What my old boss was used to were web servers spawning threads in order to process a user request. Althroug it works, it doesn’t scale very well for I/O intensive applications. The scalation problem is ultimately related to the nature of I/O described before “An I/O intensive application pass most it’s the time sending or waiting for data”. It’s computational expensive spawn threads that blocks waiting for data.

What does Node.JS do different?

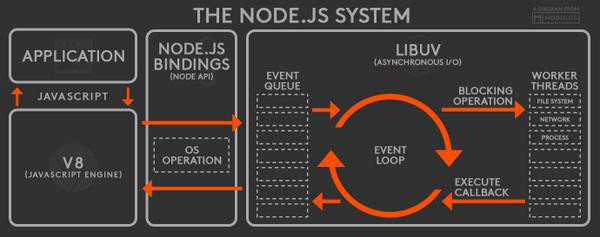

When my old boss talked about Node.JS being single thread he was actually talking about the event loop. Node.js is a runtime environment for Javascript, and the event loop is part of the Javascript model. The event loop is responsible for processing items from the call stack, those items are everything happening synchronously on our code, like for loops. One of the things the Node.js adds to Javascript is the libuv, libuv is a C library for asynchronous I/O. Libuv receives tasks from Node.JS applications and processes them in threads apart from event loop (main thread). After completition, the results are returned via their callbacks. These callbacks are enqueued in a task queue and processed by the event loop.

You might wonder what exactly is better about this approach. Node.JS applications don’t keep a thread per connection or per request, threads only process I/O tasks, it doesn’t matter if all tasks came from one user or from 100 users. If you have to start 3 I/O processes simultaneously, Node.JS parallelize this for you automatically when you keep the code asynchronous.

A Node.JS I/O intensive application

A month ago, my colleague showed his side project. It was a chatbot conversations extractor build with Node.JS, this extractor was capable of connecting to our MongoDB, extract all conversations from a period and write the data into a CSV file. This was a quick project with no intention of being performative at all. This project saved me a lot of time when I was asked to extract conversation data for a short period of time.

A couple of weeks ago, an analysis department asked me for the equivalent of two weeks of conversation data. We were in a bit of a hurry so I was trying to deliver their request as quick as possible. Turns out, our application crashed every time I submitted the extraction of a 2 weeks period. I had to extract per day and was even crashing for some days. Although I had finished what I was asked for, I thought of this as an opportunity to test how much I could improve this application performance since intentionally none was made before my changes.

What was the current state

The application expected 2 dates, and then queried MongoDB docs based on the parameters. The MongoDB collection stored docs that represents a contact and inside the documents there were a documents array with conversations between the contact and our chat bot. Every contact who had a conversation with our bot in the period given, was returned from query.

What changed (in chronological order)

The first problem to address was to avoid crashes. The question was, what was crashing our application? It turns out MongoDB was returning more data than our application could handle. This was indeed an expected behavior, Node.JS limits the RAM memory usage. The short and also wrong answer was to increase this limit right away. The first problem we found and is something that will appear again in other forms, memory footprint.

Basically, we were trying to fit all MongoDB data on our limited RAM memory resource. We didn’t need all MongoDB data at once because we couldn’t even write all this data at once, so why get it all at once? The solution was to change the way we fetch data from MongoDB to a stream based approach.

Node.JS streams

According to the Node.js v15.5.1 Documentation,

A stream is an abstract interface for working with streaming data in Node.js.

This application is using the mongoose library. This library exposes a method called “cursor()”. Let’s see the reference below. We can imagine streaming data like little pieces of data being consumed by our application in sequential order.

According to the Mongoose 5.11.11 Documentation,

A QueryCursor is a concurrency primitive for processing query results one document at a time. A QueryCursor fulfills the Node.js streams3 API, in addition to several other mechanisms for loading documents from MongoDB one at a time.

These “little pieces of data” could be the MongoDB docs we were querying before. In oppose to return all docs at once, now we divide the mongoDB docs returned as chunks and process every one of them individually. The benefits of the streaming data is the ability to process parts of the whole as soon as they arrive and a lower memory footprint. By the time the last piece of information arrives, our application doesn't need to still hold the first part in memory.

After a refactor on the way our aplication was querying data, it never ran out of memory again. It’s important to notice that the impacts of using mongoDB’s cursor it’s not only on memory but in backpressure handle too. We can define backpressure as difficult to process our data. When we process stream data, our application can adapt to the current backpressure.

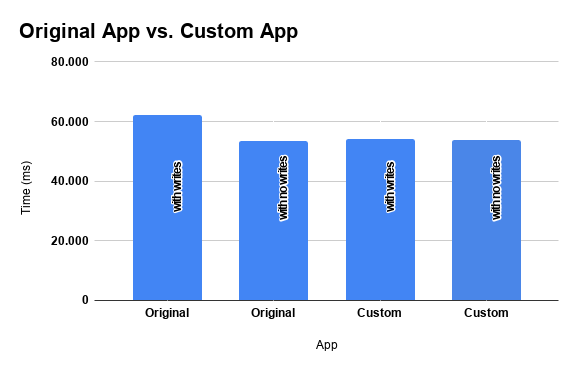

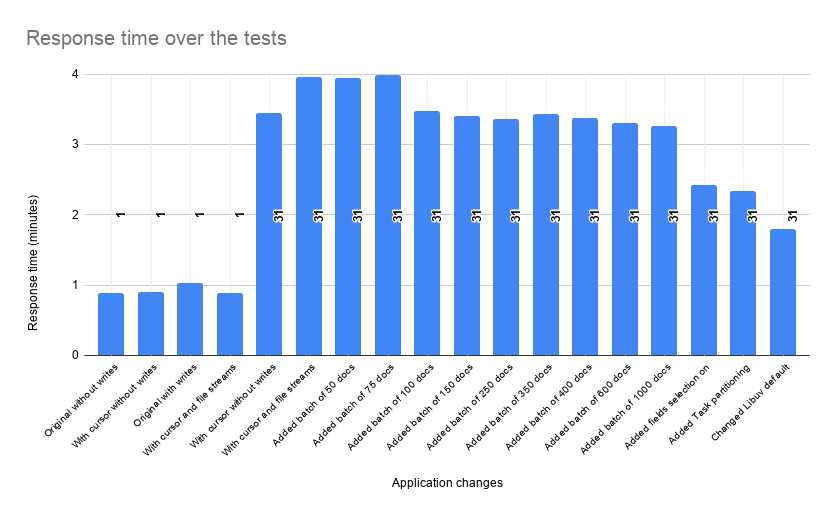

The image above shows the result of our little implementation comparing response time for extractions of the equivalent of one-day data. It’s important to note that we have a difference in response times when we are writing results but not when we are only querying them. This difference is the result of another improvement, this time on the process of writing data to a file.

Writing files with Node.JS WriteStream

Our original application was writing data to files synchronously. We already know that this process slows down our application a lot, because we were keeping I/O processes on our event loop. There is more, even if we were already writing lines to our CSV file asynchronously, we could still improve the process with Node.JS WriteStream. The Node.JS WriteStream creates a stream that writes data to a file, using this approach we are able to enqueue data to the stream, and this data is then writed to the file asynchronously. That way we again doesn’t need to keep holding all file’s lines in memory, we could send them to be writed as soon as we generate them.

It’s important to remember the backpressure concept when dealing with WriteStream. We can’t send data to a WriteStream forever, the WriteStream has an internal buffer. If the application sent the data to the WriteStream via the “write()” method, the data will be buffered, if the buffer size exceeds the highWaterMark option set in the WriteStream constructor, the method will buffer the data but return false as a result. The highWaterMark works like a threshold not a limitation to the buffer size, it’s possible to keep buffering data until the application runs out of memory.

MongoDB query Optimizations

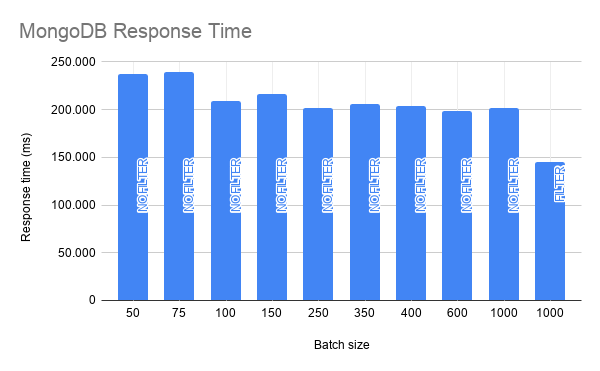

The second thing modified on the way we query data from MongoDB was the cursor batch size. The cursor batch size determines how many documents will the cursor pull from the database at first, this is only limited by the total size of the results (16MB). The image above compares query response times with different batch sizes, it helped but not a lot. What really improved overall performance was to filter only important fields on the documents, it improved our process time by almost 1 minute. The main reason was that the original version was bringing all contacts in the collection with a conversation that happened in a determined time window. The problem was that we were querying for a lot of data we actually don’t use.

It was not the case here but when we’re dealing with MongoDB, it’s important to always create indexes on the fields we’re using to query data.

Task partitioning

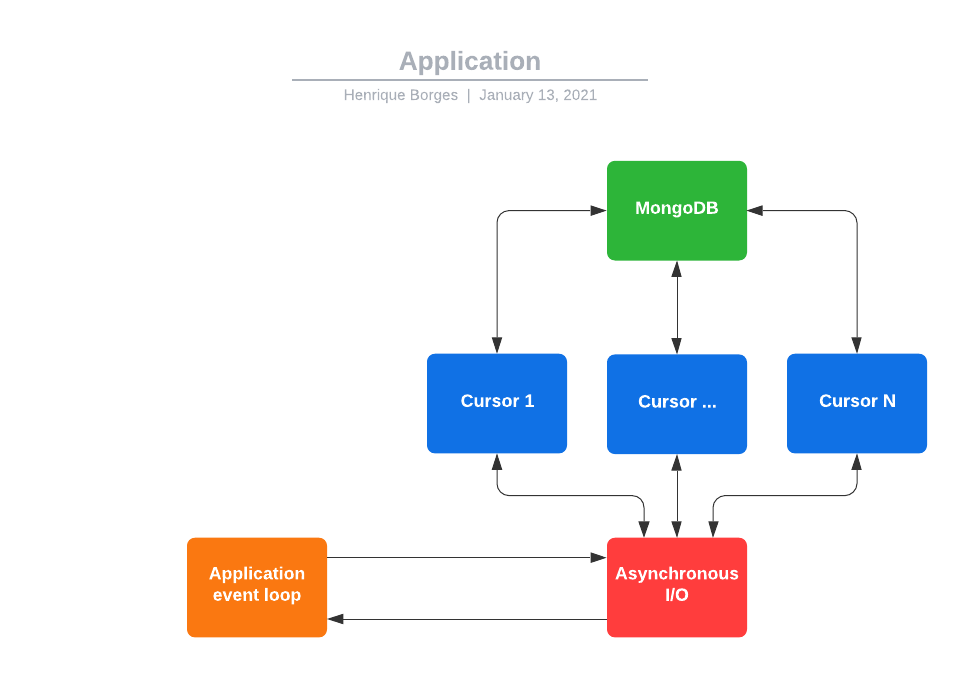

Most of what our code is doing is waiting for the MongoDB cursor to return more data. This process is limited by network latency. So the idea of this step is to split the data into multiple cursors, every cursor has its own I/O process running in parallel. So in the first cursor, our application could be processing something, on the second our application is waiting for more data and in the third one, the data just arrived.

Now we’re getting more data at the same time. Although it is important to keep in mind that a sweet spot actually exists. A lot of cursors querying at the same time could be prejudical for the database itself. Task partitioning save us almost 10 seconds of execution time. The image above compares two test querying the same data with a different number of MongoDB cursors between them.

The Libuv threads number

According to the Node.js v15.5.1 Documentation,

Because libuv's threadpool has a fixed size, it means that if for whatever reason any of these APIs takes a long time, other (seemingly unrelated) APIs that run in libuv's threadpool will experience degraded performance. In order to mitigate this issue, one potential solution is to increase the size of libuv's threadpool by setting the 'UV_THREADPOOL_SIZE' environment variable to a value greater than 4 (its current default value).

At the beginning of this post, I explained how Node.JS achieve asynchronicity using Libuv. Turns out Libuv threads are by default limited to 4 as we saw above.

process.env.UV_THREADPOOL_SIZE = os.cpus().length;This was the last tunning I did in my project and it actually helped a lot. It’s important to keep in mind that more threads don’t usually mean faster execution times. So I used the code below to lock the number of Libuv threads based on the host machine.

Conclusion

The image above contains the final comparison of the query results using 1 and 30 days queries. I wanted to test with a bigger result set, but the original version could not handle it, so for the original version, I compared just one day with a custom version using one MongoDB cursor and file streams querying also 1-day data. The response decreases in chronological order too. When doing optimizations, we often don’t find the better approach at first, we work on every little implementation, every second count at the end. I’m proud that the optimizations resulted in a processing time for 30 days of conversation data of 1,79 minutes, 2.17 minutes less than the first version using a single MongoDB cursor and file streams.

It’s pretty normal when learning Node.JS to think that async code is terrible or complicated. In fact, there are a lot of developers who are always making their code as sync as possible when it didn’t need to be. To understand the Node.JS async concept it’s what will make your code more reliable and faster. Curiously, this was not the objective of this project I worked on, it was just my excuse to challenge myself. The idea of this post was to explore and share some concepts that I thought some could not be familiar with.

Hope you enjoy ;)